A stronger and more prosperous Baltimore region.

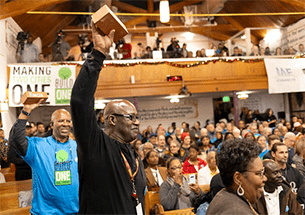

The Greater Baltimore Committee (GBC) is the leading voice for the private sector in the Baltimore region, providing insightful economic and civic leadership to drive collective impact.

Our Multi-Year Agenda

GBC offers a Multi-Year Agenda for advancing inclusive, sustainable growth. The Agenda is organized around the core pillars of Economic Opportunity, Transportation & Infrastructure, and Collective Impact.

Our Partners

Join the 400+ GBC Partners invested in transforming the economic future of Baltimore City and the six neighboring counties. GBC encompasses prominent businesses, universities, non-profits, and philanthropic organizations. Collectively, our partners are committed to contributing thought leadership, resources, and expertise to tackle our region’s most critical issues. Learn how you can get engaged today.

Tradepoint Atlantic will host our annual meeting for a once-in-a-generation night to celebrate our region's dynamic economic future. The event will feature the release of our 10-Year Regional Economic Opportunity Plan, which builds on our momentum to advance a thriving Baltimore region.